Dependence & The Enneagram | A Winter Fugitive, Part II

Enneagram, book recommendation, Part II of 'A Winter Fugitive'

Hello. This week’s issue follows a tripartite structure. I write about my experience recovering from knee surgery, and how this mirrors my personality type, as described in my Enneagram test result. The second part is a book recommendation, and finally I have left you with part II of my short story ‘A Winter Fugitive’, where the focus shifts from Australia to Italy. You can read Part I of that short story here.

#1 Dependence & asking

Gentle Reader,

They say absence makes the heart grow fonder, but what about dependence?

I’m 3 and a half weeks post knee surgery, and still in the throes of a recovery which has made me highly dependent on others. I can’t do much and I went to bed at 8pm last night, out of a mixture of boredom and tiredness.

Per se, it shouldn’t be a problem to be dependent, when I’m fortunate enough to have family who are willing to help me out and, to be honest, I don’t know how anybody would do this alone.

In the course of the first two weeks or so, it was more or less impossible for me to do anything for myself, even making a cup of coffee.

This meant that if I wanted something, I had to ask.

Asking for just about anything never came easy to me, and here, it reared its ugly head again.

Why would somebody find it hard to ask? My best guess is that in childhood, they had a bad experience with asking – an ask came with a backlash of judgement or unavailability or intimidation.

Then, when you don’t ask, you suppress. And when you suppress, you displace.

This all makes more sense, now – not long ago, at the bidding of the excellent

, I did the Enneagram personality test, which clocked me as a Type 5 (‘The Investigator’, ‘The Observer’).Scrolling down the Enneagram wikipedia page, I read the little summary chart, clipped below.

Just as the Myers Briggs personality test diagnosed me with terrifying accuracy (INTJ – ‘The Architect), here we see the Enneagram getting it right on the button. The highlighted part above designates helplessness as my basic fear – a person afraid of appearing helpless will be afraid to ask.

It checks out, as the Americans would say.

The next categories, by the way, are ‘basic desire’ (mastery, understanding) and ‘temptation’ (replacing direct experience with concepts) – these absolutely are on the money too.

But all of this is getting very deep in the weeds, reader. I recommend you take both the Myers Briggs and the Enneagram, if you are interested. If you are a user of chatGPT and if it has saved your history, you may be able to save yourself some time – I asked it to diagnose my MB and Enneagram based on my chat history, and it got it right on both counts, validating the actual tests I did online. Again, terrifying.

#2 Book Recommendation – A Pattern Language, by Christopher Alexander

Every now and then, you come across a non-fiction book which just makes sense, which jives with your own personal viewpoint.

A Pattern Language has been revelatory for me because it contains ideas which knocked around in my own brain, but 1000x more developed, and already fitted and categorised into a system. It’s as if I had been groping in the dark, only for somebody else to turn the lights on and reveal the detailed contents and contours of a room which I had imagined only in its crudest outline.

A Pattern Language was written by architect and designer Christopher Alexander and it serves as a sort of compendium of how to approach designing just about anything. It contains 253 patterns which are recursive in society, and which lean upon one another.

It’s a sort of first principles look at which aspects we should consider when designing just about anything.

It starts with very large patterns, such as how regions and cities should be organised, before coming down to smaller patterns like a front door bench.

The book states principles which are sometimes obvious. For example, in the pattern on towns and cities, Alexander states that:

“The suburb is an obsolete and contradictory form of human settlement."

He goes on to say that the magic of the big city comes from its vibrancy, whereas

“To live well in the country, you must have a reasonable piece of land of your own - large enough for horses, cows, chickens, an orchard - and you must have immediate access to continuous open countryside, as far as the eye can see.”

He expands upon how cities should be designed to optimise access to both the magic of an urban nucleus and the relaxing open plains of the countryside.

I enjoyed his reflections on home design even more. In pattern # 111, entitled ‘Half-Hidden Garden’, Alexander surmises that a front garden is not ideal, since one does not have privacy. Nor is a back garden ideal, because one feels too isolated. His compromise is that the best garden is ‘half-hidden’, a side garden where one can have privacy while also being adjacent to the street, getting the best of both worlds.

Naturally, such a garden should be south facing (patterns #105 and #161), and allowed to partially grow wild (pattern #172).

The book is full of such gems. Shout out to

for recommending it on the David Perell podcast.#3 A Winter Fugitive, Part II (read Part I here)

Italy: September

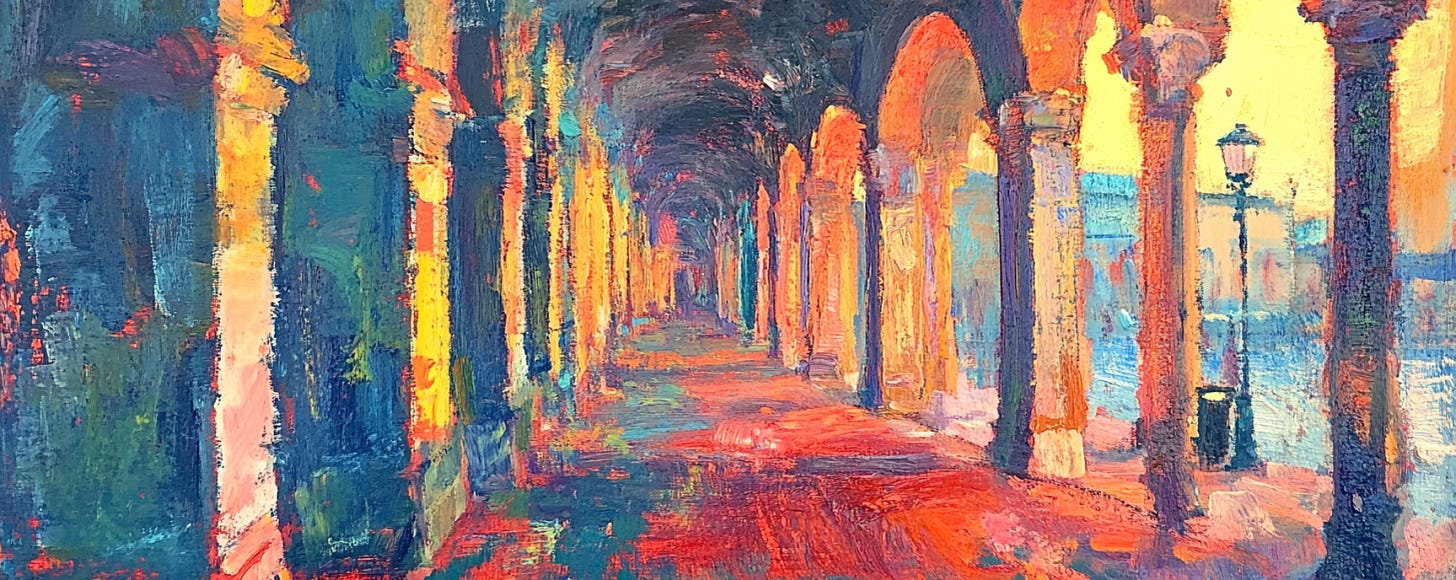

I had left the Australian winter only to burn under the too-hot sun of Italy whose heat, now in late September, was finally beginning to dissipate. There were a few last days when I needed the shade of the portici, when I hid there, kicking up red dust, and watching the city move sluggishly.

Shortly, the weather became more palatable. Then, ironically, I knew it would soon be too cold, another winter – I began to wonder if I had overstayed my welcome, if I had lost my way and forgotten my mission.

What was my mission again?

A late afternoon. I came down Via Bocca di Lupo, pausing where the alley met the main street. At this junction, my attention was arrested by a very beautiful sight – a window in the brickwork of an old wall, enclosed by wooden shutters.

They looked very ancient, the shutters, if wood could live so long, dim under the shadow cast by the profuse green of the bush which ran along the top of the wall. I love this city, I thought.

I turned left, coming onto the street where, the week before, I saw the Pope, waving to the adoring masses from a white jeep, and I came out near where she lived – I wondered if I would see her there.

Would that be a good or a bad thing? There was always a feeling that one or both of us was under a misapprehension.

Turning right, I approached the grand double doors of the Collegio di Spagna. Cast iron bars framed the lower windows of the college, darkened from where I stood; I wanted to look in, to see inside; I didn’t. No sign of life stirred from the balconies up above, only silence from the old stones, from the resolute iron scrolls that curled under the balconies.

Around the corner a young woman, not her, with big dark eyes and curly dark hair, came wheeling a bike. She wore a long overcoat; she felt the creeping chill that was starting to invade the city. I wove outside the bollards to grant her passage; I wove back in; the spokes of her bike ticked like a fading clock behind me.

Then I felt it; the winter I had fled from; it was here again.

When I reached Via Farini I remembered that, one day, when I was with her we met a giant marmalade cat, with golden eyes and a pink tongue, who suffered bypassers to stroke him, bellyup. Further along, there had been a door which she said she would put in a film scene, sturdy oak, iron fittings, a wicket-door: a door within the door. A lantern hung just above it, where the arcs intersected, and our footsteps had echoed under the portici.

What else did we see? A Madonna, muralled upon a streetcorner; the red dot of a lit cigarette suspended ghostishly at a high window. She took me down that little street, it was, she warned me, how to say, a bit - losca?

Her English failed her at times; less often than my Italian. Come si dice..?

Now, the sign on the café door tinkled to greet my entry. I took a seat out the back, on a cast iron chair in the courtyard, my favourite spot, here again. Wherever you go, there you are. Remember those Australian days?

The waitress approached me:

“Ci sei?”

Two middle-aged women paused to hear me speak, an outsider, resumed their conversation.

I ordered, then there was the vacuum, the immediacy of my work. Ought I to call it work? Pages, self-indulgent ink this time, ornate, illegible. Criss-cross, underline, arrow here, what does that say?

The self confounds you.

Plots: you lose them. They blossom, wither, die. Last resorts.

That was another time her English failed her, the night when we climbed the grand steps of her palazzo, stopping halfway to see the owner’s apartment, the wrought iron entrance, the grand hall; we marvelled, we went on, upwards. The heavy lock on her door, the cumbersome key, the lugubrious retraction of the bolt, loud and echoing on the hard floor.

All was poised.

There was a faint ashen tang of cigarettes on her breath, her hand on my chest, my hand tracking across her, before her she pulled back to say:

“No, I ‘aven’t been to the…”

A beseeching look; a silence. Views out the window, onto the street; the vasiform balustrades, concrete, of a balcony; a row of vespas in the glow thrown by the lanterns that illuminated the portici; the stillness of the witching hour.

“...estetista.”

Aesthetic, I thought. I was a B1 in Italian, a low intermediate; as a man I was an A1, a beginner, grasping and clutching.

In the cafe, I heard the waitress before I saw her.

“Un caffè macchiato.”

She clinked the little cup and saucer onto the table beside my notebook, butterflied, its runic symbols bared. Did she see? Words waxing fat.

“Grazie.”

“Prego.”

An alveolar trill. Was she impressed? She turned with heedless grace on a heedless heel. Bronze ankles peeped out beneath the wellfolded cuffs of her black jeans.

Long-legged Italy took a bite out of Sicily.

Speckled sunlight cast chance rays through the aperture, through the awning, ran prickling along my neck. The last dying rays. I took up my pen; the page took umbrage. I wanted to make amends, but we always quarrelled.

It was like Australia all over again.

Maybe it was time to go home. To my ‘real’ home. I replayed scenes from my little European escapade and I thought of the sour rubbery smell of the U-Bahn, a certain je ne sais quoi. An ich weiß nicht.

Then, there was searing greyness, spat out into a Soviet-Bloc hangover, haunted by the memory of the drug dealer who wheeled up beside me outside the nightclub, with his bipedal minder, with a lurid smile, to say: Ich hab’ alles.

I didn’t doubt him for a minute.

Affiliates:

My friend Paul Millerd runs the Pathless Path Community, a cozy online space where we support each other to find ways to live and work in the most authentic way possible.

I also recommend the Supernote e-ink device, which I use for reading, writing, and annotating documents. This affiliate link is only valid for EU customers.